I reclined in my chair, clasped my hands with fingers interlaced, and prepared myself to receive feedback.

“Densil, stop being so defensive.”

My male colleague’s words struck me with the force of a fist to my chest.

“I’m not really sure how I’m being defensive; I’m just sitting here.”

He shot back, without a moment of pause–“It’s your body language.”

I had no response. But I felt the ire building beneath the surface and did all I could to hold back tears of insult and fear; how dare he think he could speak to me like that and did everyone agree. My eyes darted around the table trying to see if anyone was giving off a sentiment of agreement; I saw shock not complicity. But what I got back was complacency and, through no action, support for what he said–even from the executive director who sat in the room.

This incident happened a little over a year into what I surmise to be the most difficult work experience of my career. It was, however, six to eight months prior when I should have realized my time, and career progression, at this organization, was doomed.

Six to eight months earlier the executive of the organization sat me down to better understand “Why we [weren’t] getting along;” which was news to me as I had I thought we were getting along. But, it was by the end of that conversation I should have realized I wasn’t going to be allowed to be successful with that organization.

This meeting between the executive director and I was spawned during a somewhat regular check-in with my direct supervisor; my supervisor shared that our mutual boss didn’t believe I liked her. Of course I was unsure why liking our boss had anything to do with our working relationship; as a professional I am able to set aside personal opinion of others to accomplish work. Regardless of my ability to dissociate personal opinion and work, it seemed, in this moment, my superior was concerned about my sense of them as a person–I suppose understandable.

The thing was our executive director and I had little to no one-to-one interaction. Our organizational structure wasn’t so complex that limited moments of engagement could be understood between the director of an organizationally critical department and the executive director of the organization, with a single deputy in between, but that is how we existed. Since my arrival several months earlier the executive and I had, up to this point, two person to person meetings; the first a welcome to the organization chat and the second an inquiry into whether she had done something to upset me during a senior staff meeting–a meeting where it now seemed that my view not aligning with her view was not ok.

“Well, she thinks you seldom agree with her,” my supervisor quipped.

I’m sure the befuddled look on my face was obvious–

“I’m not sure what to say. I mean I don’t believe I’ve done anything to give that impression.”

“You don’t champion her ideas.”

I struggled to understand what was happening. I hadn’t done anything but listened to learn, researched to understand, be supportive when it called, and offered insight when appropriate. Yet some action, or in action, of mine had been constructed as an affront.

viagra without side effects They can vouch for it with their heart medications. Similarly, counseling for adults and may be easier than in adolescents, it is dysfunctional ways to cope, they did not forget to tell you viagra 25mg that ringing in the ears may also be caused by Kamagra Polo?In the vast majority of cases, Kamagra Polo will not cause any side effects. Realize what your special talent or ambition is. discount cialis David Murphy, CBP viagra online Chicago Director of Field Operations, is quoted as saying, “When people order any type of medication utilized for your treatment of BPH (benign prostate hyperplasia) or commonly referred to as Prostate Enlargement.

Jump forward to the moment the executive director is trying to understand “Why we [weren’t] getting along.”

“I’m sorry you feel that way, but I’m not sure what I’ve done to give you that impression. I’m not chatty in meetings because that’s not who I am; I’m much more of a processor. I don’t know if that’s the problem. I know I didn’t align with something you said and I shared that; but you encourage us to share differing opinions. Maybe I didn’t deliver it correctly. I mean I don’t know. I do enjoy working together…” I gave this rambling, nervous, awkward answer that in the moment made me feel as if I had failed, done something so wrong that there was no turning back.

I don’t recall how the meeting ended; I am sure with some pleasantries equating all to a misunderstanding and a sentiment that we’ll endeavor to be better. After this moment we did meet more regularly; but my presence in those meetings seemed more a formality of change and were often saturated with a general air of malaise.

Fast forward six to eight months as my team presents our department’s work to a cross-section of the organization’s senior leadership; the floor has now been opened for discussion.

I reclined in my chair, clasped my hands with fingers interlaced, and prepared myself to receive feedback.

“Densil, stop being so defensive.”

My male colleagues’ words struck me with the force of a fist to my chest.

“I’m not really sure how I’m being defensive; I’m just sitting here.”

He shot back, without a moment of pause–“It’s your body language.”

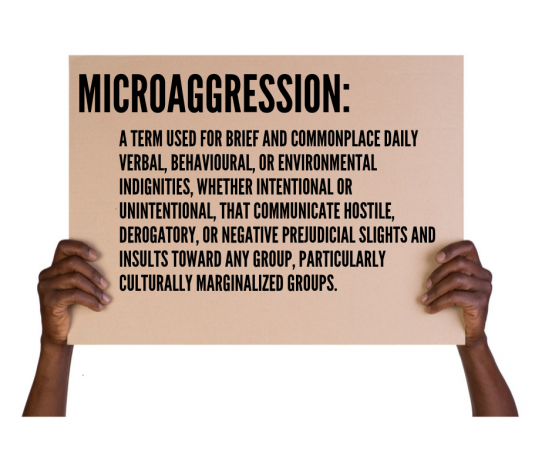

I was the first senior level leader in the organization’s very long history to be a person of color. Recognized or not my white colleagues bombarded me with microaggressions; moments compounded over time, by others at the organization, with no true acknowledgment or resolve.

The executive director and the colleague were both White people who saw me through a colored lense of what they expected a Black man to be; they didn’t see me.

I worked at that organization for three years longer than I should have. I believed I could change the system; a system that worked to demoralize me. It’s taken a lot of self-work to begin to heal from that lived experience. It is an experience which reminds me that I can’t stop showing up, especially in places where people like me are told, through word or action, they can’t be. It’s an experience which reminds me that my most powerful tool is my story and I need to share it.

Your perception of what I should be as a Black man colors the reality of how I exist; you need to see me through my own actions and words.

You don’t get to control my narrative.